In the 1980s, Hyderabad Book Trust pioneered low-cost translations into Telugu

on May 30, 2022

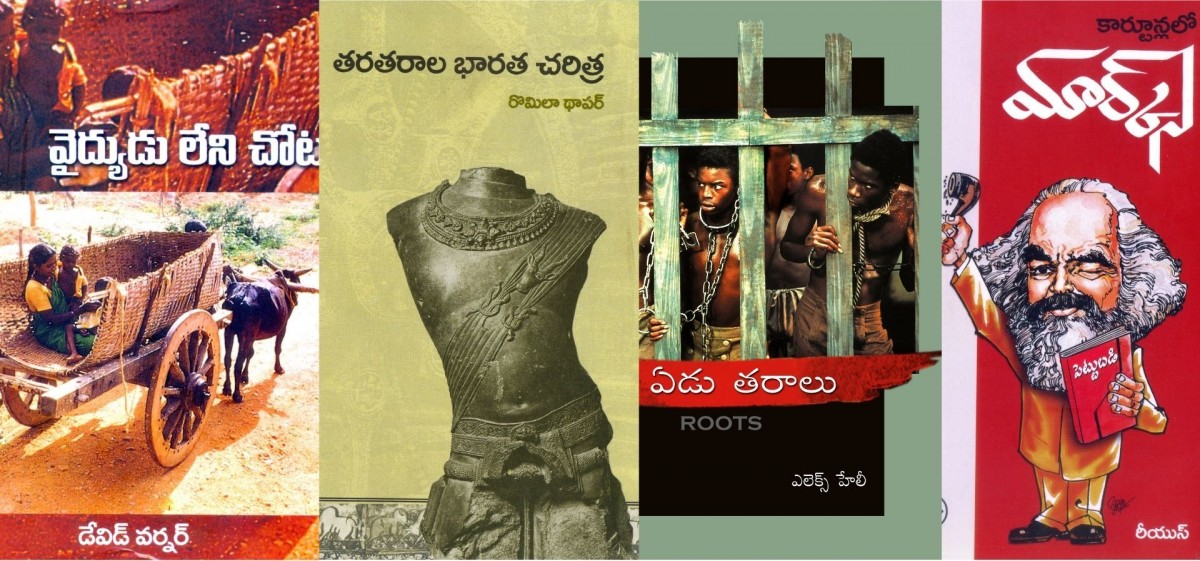

A chapter in Gita Ramaswamy's recently published memoir on life as a lapsed revolutionary, Land, Guns, Caste, Woman, is devoted to her work as the publisher of Hyderabad Book Trust. She describes how, in the 1980s, works by Mahasweta Devi, Alex Haley, and Romila Thapar found their way into Telugu.

With Geetanjali Shree's Tomb of Sand receiving the Man International Booker Prize for translation, Gita encourages us to go beyond English translations that occasionally make headlines.

My husband Cyril and I left the Marxist–Leninist movement after the Emergency and returned to Hyderabad in 1980, after spending three years underground. We met with other activists who had defected from their own ML units. We looked at numerous choices before deciding to relocate. There were many people in our situation who had similar questions to us. I travelled to Pune and Bombay to meet with groups of activists who had left various ML groupings but still wanted to work with people. Everyone was perplexed as to what to do next. Cyril had chosen to learn law and arm himself with tools to aid the movement in legal concerns. We met his uncle, former CPI–ML Charu Majumdar, about this time.

CK was imprisoned during the Emergency and decided not to rejoin the party. After 1977, he began publishing leftist literature, including Telugu translations of Mary Tyler's My Years in an Indian Prison, William Hinton's Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village, Edgar Snow's Red Star Over China, and Ted Allan and Richard Gordon's The Scalpel, the Sword: Doctor Norman Bethune. It was an odd meeting.

We were acutely aware of the lack of diverse reading and debate in the ML groups and identified the necessity for the publication of books and articles that would contribute to raise the level of debate among activists. We planned to intervene because such knowledge was not being developed in Telugu. When we eventually connected with CK, the group grew to include the veterinarian and activist Veeraiah Chowdhury, son of another communist leader, Kolla Venkaiah, and C. Bharathudu, a book enthusiast and companion of Kolla Venkaiah. On the recommendation of Shantha Sinha's father, chartered accountant Mamidipudi Anandam, we formed a trust (rather than a society or a private corporation).

He contended that trust would provide us with the most freedom, which was critical in the setting of a repressive government restricting publication freedom. We chose the name Hyderabad Book Trust to be impartial, indicating to our readers that we did not intend to polarise ideas. Arunatara (Red Star), Peace Book Centre, Navodaya (New Sunrise), and Prajashakti (Peoples' Might) were some of the names of publishing houses of the time. We wanted to avoid sending out such messages. The Hyderabad Book Trust was founded in February 1980 by CK, Bharathudu, poet and journalist M.T. Khan, Vithal Rajan, and me—Rajan had just returned from Canada and had joined the Administrative Staff College of Hyderabad. He left HBT within a month, but the others remained, and several others joined along the road.

To begin, we planned a set of three books: Rakthashruvulu (Tears of Blood), a translation of The Scalpel, the Sword: The Life of Doctor Norman Bethune, which was already published by CK's Anupama Press and was quite popular, Coolie Ginjalu (Two Measures of Rice, a translation of Randidangazhi by Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai), and Vemana Vaadam Vemana was a seventeenth-century poet and philosopher notable for his poetry that probed caste and morality using simple language and native idioms. These three volumes represented our ideological leanings (to the left) as well as our ambition to be distinct from the existing forms of the left.

To begin, we raised approximately Rs 25,000 in order to publish the three booklets. The sole payment was for printing; all other services, including editing, were provided at no cost. Our investment was small. Every month, I and another coworker, Krishna, received a pay of Rs 500. J. Rameshwara Rao, chairman of Orient Longman, generously provided us with two free rooms behind his office, which served as our office. Lakshmi, his daughter, is a good friend of mine.

Soon after, we launched a fund-raising campaign and registered members in the trust, promising them a 25% discount on all our books. We took public transportation everywhere, dragging cartons of books with us. I carried one container in each hand and my personal belongings in a sling bag. This was not tough in the beginning, but as the book list expanded, carrying twenty-kilogram boxes became impossible, resulting in persistent back discomfort. I wish I had known about ergonomics at the time.

The formation of the Hyderabad Book Trust in 1980 proved to be the most effective treatment for my depression. I threw myself into the work with zeal. I loved books, so what could be better than starting a publishing house? HBT made tremendous progress in its first several years. CK and I went around every little town, city, and large village, meeting writers, intellectuals, and activists; we built mobile book kiosks with two tables and a petromax light in the town centre. We met activists of all stripes in order to sell our books and listen to their thoughts. We ate and stayed with comrades and authors of all stripes, from the CPI to the ML, and when we were in a town or village where we didn't know anyone, we slept at the bus or railway station. All the while, we were commissioning translations and accepting original scripts. Soon after the first three editions, Edutaralu (Seven Generations), an abridged version of Alex Haley's Roots, appeared and quickly became one of HBT's best-loved and most-reprinted titles of the last four decades.

We also tried making children's books, but they were expensive and required a lot more artwork, colour, better paper, and a new marketing network, so we dropped the concept.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.